Migrants in Italy face uncertainty after far-right prime minister’s win

ABC NEWS – Meloni’s election last month will move the country to the far right for the first time since Benito Mussolini’s fall during World War II.

There are about 5 million foreign-born residents in Italy.

Voters in Italy elected Giorgia Meloni, the leader of a far-right political party whose roots date back to post-World War II neo-fascists.

Giorgia Meloni, leader of Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy), will become the first female prime minister in Italy’s history.

Her election last month will move the country to the far right for the first time since Benito Mussolini’s fall during World War II. The Brothers of Italy, which was founded by Meloni, is a national-conservative populist party that opposes undocumented immigration, according to its website.

Meloni’s victory now means uncertainty for those who migrated to Italy.

When Baryali Waiz, a refugee in Italy, heard the results of the general election, he said he was worried.

“What happens when voters can’t find work? They blame migrants,” Waiz told ABC News.

As of August, Italy’s unemployment rate stood at 8.1%, the third highest in the European Union after Spain and Greece.

Clamping down on immigration was a key part of Meloni’s campaign. Though she softened her rhetoric before the election, Meloni pledged stricter border controls and proposed establishing European Union-managed centers to analyze asylum applications.

There are about 5 million foreign-born residents in Italy, making up less than 9% of the country’s total population of 59.2 million, according to the country’s most recent census data. Poll results from 2018 concluded that 35% of Italians believe immigration was one of the most important issues facing their country, an increase of 17 percentage points from 2014.

Meloni has called for a “naval blockade” at sea to prevent “illegal departures” to Italy. She opposed “Ius Scholae,” a bill proposing citizenship rights for students under 12 who immigrate to Italy for their education. Meloni has referred to pro-immigration measures as part of a left-wing conspiracy to “replace Italians with immigrants.” During a speech in January 2017, she called immigration to Italy “ethnic substitution.”

Waiz, 30, has lived in Rome since he was 16. He attended Italian high school and studied political science at John Cabot University. Originally from Kabul, Afghanistan, Waiz said he’s grown accustomed to anti-immigration sentiment in Italy, which he said has become more normalized since Meloni came onto the political scene.

“She’s using the weak points of the Italian people — religion and hate,” Waiz said.

Branding herself as a Catholic mother during her campaign, Meloni’s victory in Sunday’s general election coincided with the Catholic Church’s World Day of Migrants and Refugees. Meloni capitalized on preexisting fears regarding the declining birth rate in Italy, which remains at 1.2 children per woman.

“Meloni’s anti-immigration views are always framed into Italian identity, centering on family and markers of religion,” said Andrew Geddes, director of the Migration Policy Center at the European University Institute in Florence. “Foreigners and outsiders may not fit with that identity.”

Meloni’s rhetoric is seldom about the contributions of migrants, who deliver services in the Italian economy, Geddes said.

European bureaucracy will temper Meloni’s ability to enact anti-immigration measures, Geddes noted. For instance, her idea of naval blockades would, in practice, force migrant boats to dock in Spain or Malta, creating tension within the EU. Over the last four decades, the average life of a coalition in Italy has only been 18 months, Geddes said.

Though it’s unlikely Meloni will radically alter a complex system of immigration rules, her direction will accelerate major societal transformations, said Alberto Alemanno, a professor of European Union Law at HEC Paris.

Born in the northwestern Italian city of Torino, Alemanno returned to Italy for the past week, where the social cohesion with immigrant communities is “eroding,” he said.

[Meloni] makes racism and xenophobia mainstream, which is negative for Italy’s investment in European multilateral relations. Her governance will also make it more difficult for nonprofits and legal firms to aid immigrants in Italy.

Alberto Alemanno

Restrictive policies in Italy’s legal framework will be an uphill battle for asylum seekers, said Pietro Derossi, head of the Global Mobility & Immigration team at Lexia Avvocati, a legal organization in Milan. Migrants fleeing from poverty, persecution or war will be adversely impacted by Meloni’s election, Derossi said.

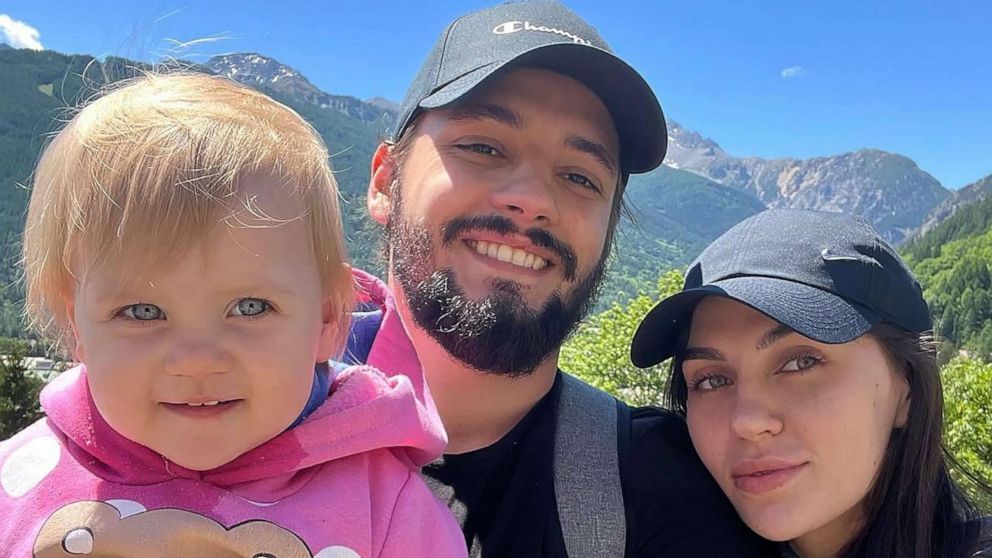

One of Derossi’s clients, Igor Makushinksy, is a Ukrainian citizen. Since Makushinksy entered Italy before Feb. 24, he is ineligible for temporary protection for Ukrainians. Neither Makushinksy nor his wife and newborn daughter have been able to find permanent residency. His family cannot benefit from medical and social assistance without documentation.

“We have three EU countries in which the far right is dominating now,” Makushinksy told ABC News. “It scares me.”