Will COVID-19 spark reform of the EU’s borderless Schengen Area?

EURONEWS – Several EU countries are moving to reinstate border checks and travel restrictions over a troubling surge in coronavirus variants.

Several EU countries are moving to reinstate border checks and travel restrictions over a troubling surge in coronavirus variants.

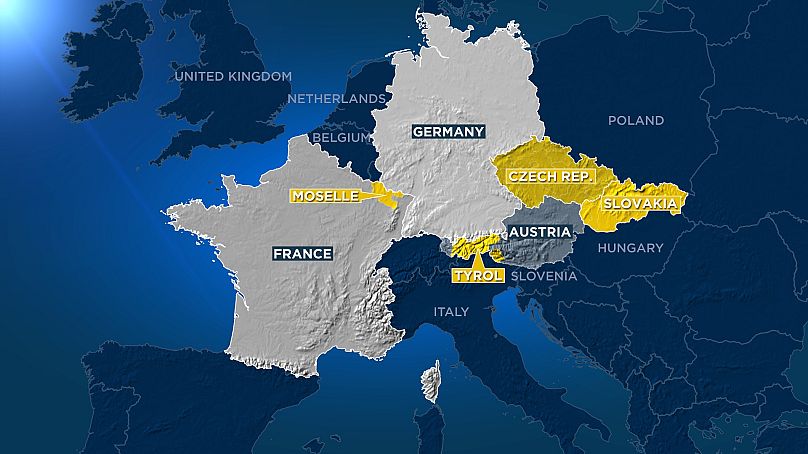

Germany announced on Sunday that travellers from France’s northeastern Moselle region will face additional restrictions because of the high rate of South African variant cases there.

The developments at the French-German border are only the latest in a long series of Schengen exceptions in several countries including Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Hungary and Sweden.

The situation recalls the much-criticised first wave of the pandemic, when EU countries hastily closed their borders to each other in March 2020 without coordination.

So, will variants deal the final blow to the passport-free Schengen Area, a pillar of European integration?

Euronews looks at the recent internal border measures and what they mean for the future of the free movement zone.

What is Schengen?

Hailed as “one of the greatest achievements of the EU”, Schengen is “an area without internal borders, an area within which citizens and many non-EU nationals staying legally in the EU can freely circulate without being subjected to border checks”, according to the EU Commission.

The Schengen zone currently comprises 22 of the EU’s 27 member states as well as four non-EU members: Norway, Iceland, Switzerland and Liechtenstein.

Croatia, which joined the EU in 2013, is one of five members not in Schengen, alongside Ireland, Bulgaria, Romania and Cyprus.

The Schengen zone was created in 1995.

Which restrictions have been put in place over Covid variants?

Belgium banned all non-essential travel to and from its territory in late January. The measure has been extended until April 1.

Germany partially closed its borders with the Czech Republic, Austria’s Tyrol and Slovakia in mid-February.

Germany’s Robert Koch Institute said on Sunday it would add the French region of Moselle to the list of “variant of concern” areas.

France said it regretted the decision and negotiated with its EU neighbour to lighten the measures for 16,000 inhabitants of Moselle who work across the border.

Instead of the daily PCR virus tests that Germany has applied elsewhere to travellers along some borders, Moselle residents will need to present a test — PCR or antigen — conducted less than 48 hours before the crossing.

French MEP Fabienne Keller (Renew Europe), who is also the former mayor of Strasbourg, told Euronews the measure required a drastic increase in the volume of tests and “a lot of resources.” “Is that reasonable in terms of epidemiological impact? I don’t think so,” she said.

According to the lawmaker, some territories have developed across borders as “little Europes”, living spaces where national frontiers are irrelevant. “These territories need to be better taken into account in the health crisis,” she said.

Denmark, Finland, Hungary and Sweden are also among the six EU countries that have been urged to lift border restrictions in a letter sent by the EU Commission last month and seen by AFP news agency.

Are the restrictions legal?

While free movement is the rule in the Schengen zone, EU law foresees exceptions in case of “threat to public policy or internal security.”

Alberto Alemanno, a professor in European Union Law and Policy at HEC Paris, told Euronews that member states were allowed to enact such restrictions if they were “justified” and “proportional” to the threat invoked.

But according to the legal expert, recent border measures do not fulfil the above criteria, which is what prompted the EU Commission to send a letter of warning to six EU countries.

The correspondence sent on February 23 to Belgium, Denmark, Finland, Germany, Hungary and Sweden, pointed to a risk of “fragmentation and disruptions to free movement and to supply chains”, according to a European Commission spokesman.

It noted that the spread of variants in the Czech Republic and Slovakia — which were in Germany’s “list of variant concern areas” — was no worse than in some other EU countries.

The criticism has drawn pushback from Germany.

“I reject the accusation that we have not complied with EU law,” German European Affairs Minister Michael Roth said.

German Interior Minister Horst Seehofer told Bild newspaper that the European Commission had “made enough mistakes” and “should support us and instead of putting a monkey wrench in the works with cheap advice”.

What can Brussels do?

The European Commission has given the six countries 10 days to respond to its letter, after which it could theoretically trigger sanctions for breaking EU law.

But according to Alemanno, “the Commission will not have the courage to go all the way”.

With the health situation deteriorating, a judicial follow-up would be politically very delicate and thus unlikely, the expert told Euronews.

“It would be difficult but never say never,” Marie De Somer, a senior policy analyst and head of the migration and diversity programme at the European Policy Centre, told Euronews, noting that tensions over borders between the EU executive and Belgium and Germany were running high.

She added that the Commission should have started Schengen-related infringement procedures before — during the first wave of the pandemic in March 2020 or the migrant and terror crisis in 2015-16.

“If it starts now, why didn’t it start before?” she wondered.

“What the EU Commission is doing correctly is highlighting its concerns to the member states,” De Somer said.

Doorstep EN | I am participating in the #GAC this morning to recall the importance of a coordinated approach to restrictions on free movement. ??@EU_Commission has also written to 6 MS to obtain more information on the measures taken. #COVID19 @EU_Justice pic.twitter.com/cRDEZ8rc0R

— Didier Reynders (@dreynders) February 23, 2021

“The Commission wants to recall to the member states that it is a necessity to go back to a coordinated approach (…) in relation to the free movement of people and goods,” EU Commissioner for Justice Didier Reynders said on the day the letter was sent.

“We ask all member states to go back to a correct application of the recommendation adopted by the Council”.

But the recommendation adopted late last year is non-binding and there is little the EU executive can do against member states not implementing it.

Have EU countries learned the lessons from the first wave?

“Last spring we had 17 different member states that had introduced border measures and the lessons we learned at the time is that it did not stop the virus but it disrupted incredibly the single market and caused enormous problems,” EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen told reporters last month.

In practice, however, Alemanno told Euronews that EU countries had not learned those lessons and that Schengen was again “de facto” suspended.

The assumption in many EU countries is still that border closures can limit contamination, the professor said, which he called “an illusion”.

On a more positive note, Keller and De Somer noted that the restrictions recently enforced to counter the rise of variants were not as extensive as those put in place during the first wave of the pandemic.

“What we are seeing today is not as bad as in March and April,” Keller told Euronews, recalling endless queues at the French-German border last year.

There is more dialogue, the lawmaker continued, noting that local authorities in her region consulted regularly with their counterparts in neighbouring German states.

“We’re making progress,” Keller said. “But we have not yet reached the stage of taking into account cross-border regions as integrated living spaces.”

There were also further attempts to coordinate the response of EU countries with meetings at the EU Council, even if this coordination is “not where it should be”, De Somer added.

“We still see member states going at it alone, which is a worrying sign,” the expert said.

Can Schengen survive the latest wave of restrictions?

“Schengen will come out very weakened” of the current crisis, Alemanno said, noting that it was already “not in great shape” before.

The migrant crisis and terror threat pushed many countries to throw up internal border checks and temporary security controls in 2015 and 2016.

Coronavirus “made it even more obvious that some states are using borders to meet political ends”, the expert told Euronews.

The new restrictions create a “precedent” for EU countries willing to erode free movement, he continued.

“The reality of a borderless union can be forgotten in the foreseeable future,” Alemanno said.

De Somer said that during the first wave of the pandemic, border checks stayed in place for longer than necessary. “If we see a similar trend this time, the risk is that border checks become the new normal,” she warned.

Reforming Schengen?

In a note published in June last year after the first wave of the pandemic, the Schuman Foundation, a think tank, recommended that the EU “clarify the legal framework [of Schengen] and provide the institutions with the tools to ensure that it is respected, in the interest of the Union, of its values and of the rights of its citizens.”

De Somer said that the current legal framework was “burnt” due to a lack of clarity and enforcement, “which is why it is not a bad idea to start on a new basis.”

The European Parliament has called on the Commission “to propose a reform of Schengen governance” and “ensure a truly European governance of the Schengen area”.

A new EU legislative package on Schengen is expected this spring, Keller told Euronews.

But reform projects floated by some EU leaders are likely to move towards stricter controls rather than more open borders.

Last year, French President Emmanuel Macron urged the EU to reform the Schengen area, saying the pandemic and the terror threat called for change.

For Alemanno, a regional approach would be more rational than relying on nation-states and their borders to control the pandemic.

It is also essential that policy-makers take into account the needs of the 20 million European citizens who live in another EU country than theirs, as well as those of cross-border workers, the expert said.

“They embody the European project,” Alemanno said and yet “they are not taken into consideration”.